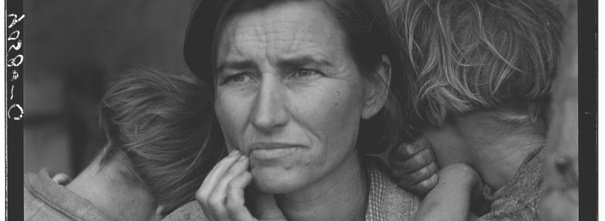

More than we can see—Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’

In 1918, at age 23, photographer Dorothea Lange moved herself and her evolving portraiture skills from New York City to San Francisco, where she opened a successful commercial studio that also became a salon for local artists to gather, one of whom, landscape painter Maynard Dixon, she eventually married. The specific image that comes to mind among people who recognize Lange’s name, Migrant Mother, was made outside the studio, however, eighteen years later. It is one of thousands she took while working on a government-funded project in collaboration with sociologist (and second husband), Paul Taylor, to document the poverty and poor working conditions of California’s migrant farm workers. This iconic portrait of a poor white woman surrounded by her children, looking off in the distance with an expression somewhere between unknowing and worry, became a symbol of the anxieties of a nation during the Great Depression. As I learned more in Linda Gordon’s biography of Dorothea Lange, A Life Beyond Limits (NY: WW Norton, 2009) about the history this photograph, I reconsidered my own photography practice in light of hers.

Lange’s photographs of migrant farm workers were taken to create sympathy for the miserable conditions in which they worked and lived, even as she imbued people in the fields with as much pictorial beauty as she had her customers the studio. Her documentary purpose, however, meant her images required more context than her studio work, requiring longer shots that included more of the landscape the workers were inhabiting. She used captions to convey important information about the lives of the people she was shooting. Author Linda Gordon writes, “she did not want her photographs to be timeless insights into human universals. In Lange’s own words, ’Every photograph...belongs in some place, has a place in history--can be fortified by words. I’m just trying to find as many ways as I can to think of to enrich visible images so they mean more.’ Gordon goes on to say that Lange’s “captions were substantive, not literary, and they did not repeat information in the photograph.”

Taylor’s social science research papers that her photographs were meant to buttress were useful in arguing for specific policy reforms, but the details of specific people’s lives in Lange’s captions were meant to intensify the viewers’ empathy. Lange’s caption for Migrant Mother, “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two,” tells the viewer that this woman is younger than she looks and her burden is even heavier than we might see in the image.

-- o --

I struggle myself with how best to use words and pictures together. I’ve thought, too, that they often need each other but my concern has been about how one medium might restrict the meaning conveyed by the other--particularly how words would change the meaning of the images. Which is more important? Which should come first for the person who experiences the content? Do I want the viewer to construct a truly idiosyncratic meaning for the image or do I want to influence it with mine?

I am convinced by Lange’s words now that if the purpose is documentary work, this question doesn’t really make sense. I am more concerned that more context be given. Words and pictures belong together, though each should provide information that the other does not. Visual data processing generally dominates verbal data processing. When pictures and words are presented simultaneously in a book or in an exhibit, most viewers process the visual image first and then use the words to further make sense of what they are seeing.

Lange and Taylor’s collaborative book about their work together on the plight of Dust Bowl migrants, An American Exodus (NY: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1939), illustrates Gordon’s description of their work as a tripod of “photographs, captions, and text.” Learning about Lange’s conscious use of captions, and thinking of captions as a category of words distinct from essay text, has been helpful to me in giving more weight to the utility of captions and in considering how best to use each in conversation with photographs.

— o —

And yet, there is still another issue to consider, specifically as it relates to photographs of human beings. Lange’s caption gives us more information about this migrant mother, but is it our business? She is a real person, not as a symbol. There is even more to know about Migrant Mother than what Lange wrote in the (rarely used) caption. The woman’s name was Florence Thompson. She was born in Oklahoma. She’s Cherokee, not white. She moved with a husband and five children in the 1920s to California, where she was widowed and remarried and eventually had five more children. The day this photograph was taken, Lange had learned that a freak cold snap had killed the pea crops, so there was no work for workers like Thompson and her family. Lange stopped by the Nipomo camp thinking there would be idle farm workers there. When got out of her car, she saw Thompson, whose husband was away with their sons getting the car fixed. Lange promised not to publish Thompson’s name with the photograph. Readers of the San Francisco Chronicle, where it was first published a couple of weeks later in March 1936, responded with $200,000 in donations for farm workers who were stuck in Nipomo because of the ruined crops. Lange never personally made money from any specific image taken for her government grant work, including this one.

Thompson felt embarrassed and betrayed when she first saw the photograph over two decades later, in US Camera magazine. By that time, as public property, it was available for any person or organization to use without a fee. Thompson believed she had been promised it would never be published, period, and that Lange had personally profited financially from it. Lange, of course, did profit from it reputationally. Lange was taken off guard by Thompson’s strong reaction. The nuances of why Lange had not understood how her photograph might cause potential harm, nevertheless, stand in juxtaposition with how it actually did. A photograph without a name attached to it is not anonymous when the subject is clearly recognizable; to think it so is evidence of class bias.

Many photographers are careful to get written permission from people whose faces they want to use in their work, but the social ethics beyond what is implied by written consent must still be considered in every portrait. What is the purpose of the photograph, and who benefits? What is the power dynamic between the photographer and the subject that may make even an image with written consent seem coerced? How does the subject understand what is being described as the potential uses of the image to be captured? Where is the possibility of negotiation between photographer and subject once it is processed for viewing?

Even if it is legal to publish photographs taken of people in public spaces, is it always the right thing to do so? In thinking about how Thompson felt when she learned she had become the public face of misery (even if beautifully rendered), I believe photographers must always have this conversation with people they photograph—with the exception perhaps of celebrities when they are performing celebrity. It is a difficult conversation to have, logistically and emotionally, and it is the reason I rarely take candid photographs of people I do not know, or share publicly the ones I have taken. I am most comfortable with photographs in which my subjects are looking directly into the camera, so I (and others) know they know they are being captured on film. Perhaps captions should include a statement by photographers about how they met the subject and what they agreed to about the use of the image.

— o —

I enthusiastically recommend Linda Gordon’s book, Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits (WW Norton, 2009)—especially for photographers who have an interest in using their art form for social justice—and also for women negotiating the tensions and stresses of combining motherhood and work. I learned so much about Lange’s complex story from reading this thoughtful, well-written account, set within the social and cultural landscape of the early 20th century America that informed her life as artist, social activist, daughter, wife, and mother.