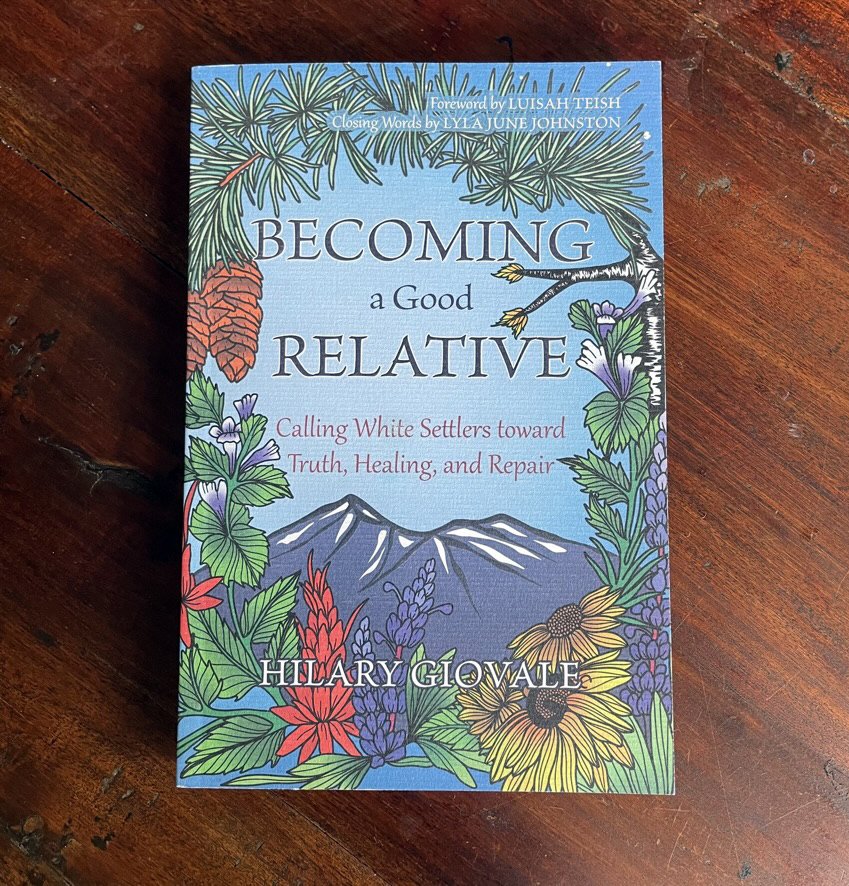

Book Review: “Becoming a Good Relative: Calling White Settlers toward Truth, Healing, and Repair,” by Hilary Giovale

Hilary Giovale’s book, Becoming a Good Relative, is a gift and an invitation. The gift is the story of her journey into relationship—with Indigenous, Black, and People of Color whose paths she finds herself walking along—but also the story of finding relationship with her European ancestors who come to her along other paths, sometimes unbidden. As she develops bonds of trust with the people she meets, they tell her of the embodied trauma that continues in their lives, generations since the beginning of (and never really ending) colonial land theft and genocide, she begins to understand her own ancestors’ participation in the white settler colonization project. She finds the threads of connection with her ancestors entangled with her new understanding of the social injustices in the lives of others.

Hilary’s first encounter with her European ancestors occurs during a trip to Scotland with her extended family. They visit the island of Erraid where she experiences the unnerving sensation that she has been there before. As they move on to Balquhidder, she finds her family name on the wall of a small stone church. She is drawn to climb up a hill behind the church, where she once again feels herself connected to a place she’s never been. Carrying the knowledge of this strange, physical awareness deep inside of her, she later uncovers, almost accidentally, emotionally devastating truths about a descendant of these same ancestors who immigrated to America in the 1700s, a fourth great-grandfather who enslaved people to work for him in North Carolina and Mississippi.

This is not only a story about the guilt and shame from that discovery, but also of reckoning and reconciliation. She finds the political, social, and cultural histories of this country that have been largely hidden, that caused past and current suffering of Indigenous, Black, and People of Color. Deep feelings of grief and anger arise in her. Though she might have expected blame and judgement from friends who started her on her exploration, instead she finds love and solace. They share with her ways forward into forgiveness and repair.

Key to this process was finding identity with her own ancestral relations, the relatives that she could have easily only blamed for her feelings of humiliation when learning their complicity in others’ suffering. Instead she sought out information about their lives in Europe, the trauma, especially for women, that was passed down to descendants and onto whoever was “the other,” in their new homelands. She was encouraged by Indigenous friends to learn from the cultural/spiritual traditions of her Scottish/Celtic ancestors as a way of finding love and affection and sympathy, honoring and celebrating the good that came to her from these ancestors. When Hilary felt the need for European-descended Elders to follow this path, she found Sine McKenna from whom she learned language and stories and songs. Hilary wrote, “I could sense ancestral memory reweaving within my blood and bones…some of the Gaels’ ancient cosmology was still imprinted within the old songs, blessings, and cures” (p.139).

This loving reconnection that gives her a new depth of understanding of herself does not obviate the need to apologize and make repair. Through her ever-evolving developing relationships with Indigenous, Black, and People of Color she finds ways in which present day amends can be made for unearned privilege. Sometimes this takes the form of service, such as assisting with fasting ceremonies or working in solidarity to change unfair policies, and reparation sometimes takes the form of money or land. Making repair is an ongoing practice.

The invitation of this book is made to descendants of white settlers, to join her in this work of revelation and repair, beginning from wherever we are. She provides a multitude of resources to assist in every aspect of our journey toward becoming a good relative. She introduces us to so many teachers and writers who have laid the groundwork for understanding the landscape of the past and the present, and gives due credit to the many people she knows personally who supported her along her path, including the ancestors she met along the way.

I am glad to say that I know Hilary through my participation last year in the “Rekindling Ancestral Memory Circle” co-facilitated with Elyshia Holliday, Executive Director of ONE, the organizational host. This nine-month workshop guides white settler descendants through a process similar to hers. In the workshop I learned parts of Hilary’s story, but I was eager to read the fuller story. Through the narrative generosity of this book, I came to understand how her work unfolded over time. I was reminded, through her example, that the work of social justice, of investigating the past, and working towards repair in the present are not tasks we can undertake alone. And once we set out on our journey to discover our place in all of this, we can’t know ahead of time where road will take us, only that the journey will never really end. I am grateful to Hilary for sharing all that she has learned along the way.

— o —

You can find out more about this book on Hilary’s website here. And you can follow Hilary on Instagram at @hilarygiovaleauthor.